The Maryland State Flags

by Ian Williams Goddard

Historic Timeline (1622 - 1904)

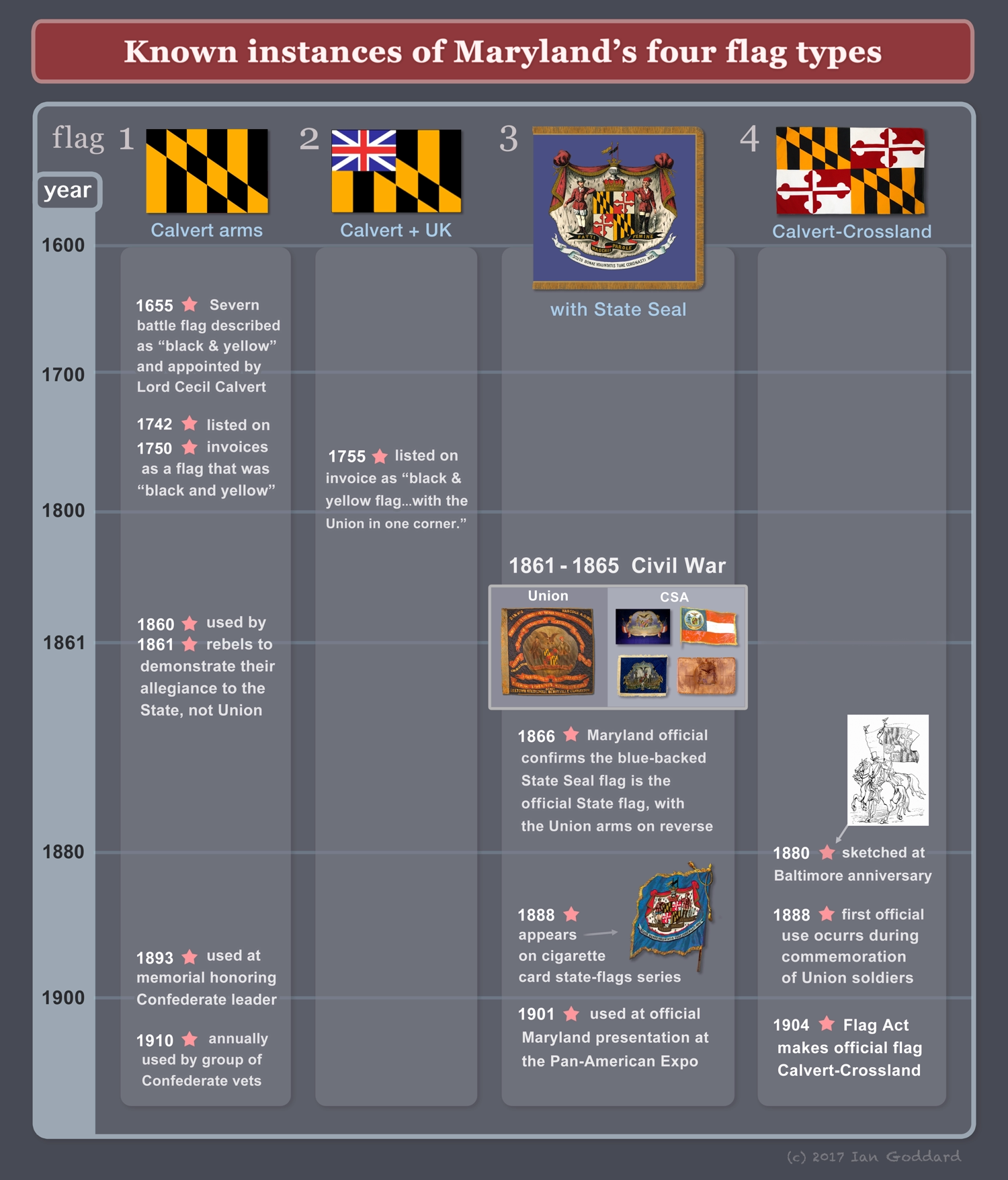

The following timeline chronicles the origin, evolution and permutations of the symbology appearing in various Maryland flags used during the state’s history, from its colonial origins until 1904 when the current Maryland flag was defined in law, the first time any flag for the state had been so defined. Prior to that, a “Maryland flag” could have been one of up to three different flags.

Year 1622 |

|||||

1622 - The Norroy King of Arms at the College of Heralds issues a coat of arms to Sir George Calvert, the first Baron Baltimore and father of Cecil Calvert.

George Calvert’s arms appearing on a letter of his dated March 9, 1623. George Calvert died in 1632. Initially George was intended to be granted the Charter of Maryland, but due to his death, it was granted to his first son Cecil Calvert instead. See: Coakley (1984) Maryland Historical Magazine, p 259 and Wikipedia: George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore. |

|||||

| 1632 - King Charles I of England grants the Charter of Maryland to Cecil Calvert. In addition to becoming the first Proprietor of Maryland in this year, due to the death of his father George Calvert, Cecil also became the second Baron Baltimore. A significant year for Maryland’s first Proprietor. See: Carr, 1984, page 5 and Wikipedia: Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore. |

|||||

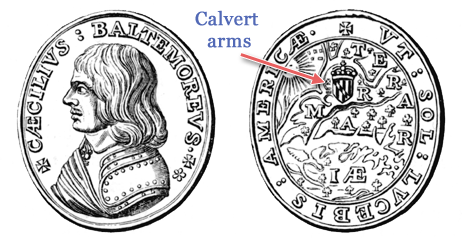

1632 - Cecil Calvert struck a medal with a map of the Province of Maryland on the obverse side upon which his Calvert-family arms appears, rather than his quartered Calvert-Crossland arms.

See: Papenfuse, Edward, Maryland State Archives and Wikipedia: Province of Maryland |

|||||

1634 - Two ships, the Ark and the Dove, traveling from England arrive in the Maryland Province.

The Ark and the Dove brought 140 English colonists to Maryland. James Thomas describes their arrival thus:

Thomas, JW. (1913) Chronicals of Colonial Maryland, page 9. According to Bozman, “the colours were brought to shore, and the colonists were all paraded under arms.” In other words, the colonial flag was brought to shore and the colonists paraded thereunder. See: Bozman (1837), History of Maryland, page 31. | |||||

1635 - Provincial Maryland map entitled “Noua Terrae-Mariae Tabula” includes Cecil Calvert’s arms, in this case with a quartering of the Calvert and Crossland family insignias, the same quartered insignia emblazoned upon today’s Maryland flag.

Cecil Calvert’s arms with quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia appearing on colonial map of the Province of Maryland. See: Tittmann (1909) Report on the Resurvey of the Maryland-Pennsylvania Boundary, p 110 and Papenfuse & Coale (1982) Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, p 6. |

|||||

1638 - The colonial flag of Maryland was used during a battle at Kent Island. Cecil Calvert’s brother Leonard took part in the battle and in a letter told Cecil that they marched “with your Ensign diplayed.” Leonard gave no further clue about the flag used. Because Cecil’s ensign was either Calvert or Calvert-Crossland, Leonard could have referred to either. However, the only surviving descriptions of colonial Maryland flags match their displaying only the Calvert ensign (see 1655, 1741 and 1749).

The Colonial Flag of Maryland Flag insignia were hand-sown at this time, so the greater complexity of Cecil’s quartered ensign might have disfavored its reproduction by hand-stitched cloth if anyone had contemplated a flag for the colony like the one used for Maryland today. See: Maryland Historical Magazine, 4(1), p 222 and the full letter in MHS (1889) The Calvert Papers, p 185. |

|||||

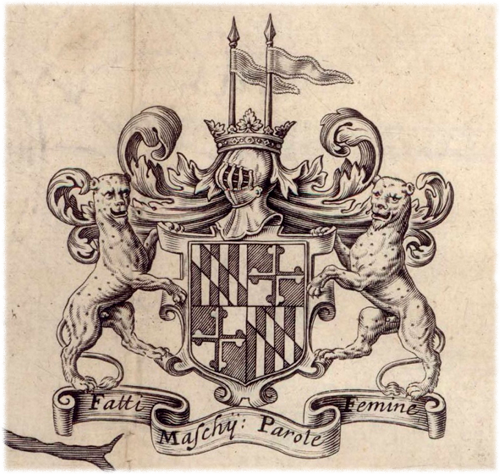

1642 - Cecil Calvert’s Lesser Seal at Arms with the quartered Calvert-Crossland shield.

Cecil Calvert’s Lesser Seal at Arms This Lesser Seal was used on Maryland laws and has two leopards as support rather than the farmer and fisherman depicted in the Great Seal of Maryland. So this Seal was Cecil Calvert’s personal arms not modified into the symbol of his province. See: Thomas (1913), Chronicles of Colonial Maryland, p 229 and Hall (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, p 27. |

|||||

1644 - The first Great Seal of Maryland is stolen during the rebellion of Richard Ingle and was lost. According to Cecil Calvert, the Great Seal was “treacherously and violently taken away by Richard Ingle, or his accomplices, in or about February A.D., 1644, and hath ever since been so disposed of it cannot be recovered.” It is believed that Ingle’s men tossed it into the St. Mary’s River. See: Hall’s, The Great Seal of Maryland and Maryland Pirate and Rebel and Wikipedia: Richard Ingle | |||||

1648 - From England, Cecil Calvert sends a second Great Seal to Maryland to replace the first, which had been stolen in 1644. The heraldic insignia upon the shield in the Great Seal is Cecil’s quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia. According to period description of the second Seal, it differed only slightly from the first, but exactly what that difference is unknown today, with no trace of the first Seal. See: description of 1648 Seal by Cecil Calvert himself, here on page 652. |

|||||

Year 1650 |

|||||

1654 - 1658 - The Puritans under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell seized control of Maryland and its Great Seal. In 1882, a committee of the Maryland General Assembly concluded that Cromwell’s commissioners had lost the second Great Seal in 1854, stating:

Maryland General Assembly, Select Committee on the Great Seal, 1882 However, historians Clayton Hall (1885) and James Thomas (1900) opined that it is uncertain if Cromwell lost the 1648 Seal, with Thomas favoring the likelihood of the second Seal having been recovered from Cromwell, contra the Committee’s conclusion. Whatever the case may be, there is today only one surviving set of dies for Maryland’s colonial Great Seal, see 1658 below. |

|||||

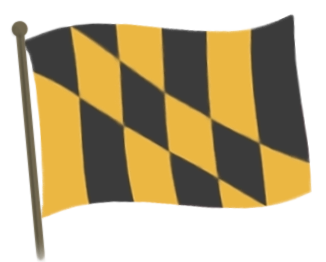

1655 - The colonial flag of Maryland was used in the battle of Severn. Battle eyewitness Roger Heamans said of the flag: “the colours were black and yellow, appointed by the Lord Proprietary.”

The Colonial Flag of Maryland In citing only black and yellow, Heamans’ description is consistent with that colonial flag being adorned only with the Calvert-family insignia rather than today’s quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia. Contrary to claims of some like historian James Thomas that today’s Maryland flag was used back to colonial times, there is no known record of a colonial flag adorned by anything other than the Calvert-only insignia with the only variation being the addition of the British Union Jack in the upper corner (see 1755 below). And yet on paper in colonial times, we almost always see the quartered Calvert-Crossland arms used, perhaps because the complex quartered desing was easier to illustrate than sew by hand into a flag. See: History of Maryland, page 220; Spencer (1914), Provincial Flag of Maryland, page 223; Thomas, 1913; Browne, 1884; Maryland, The History of a Palatinate, page 81 | |||||

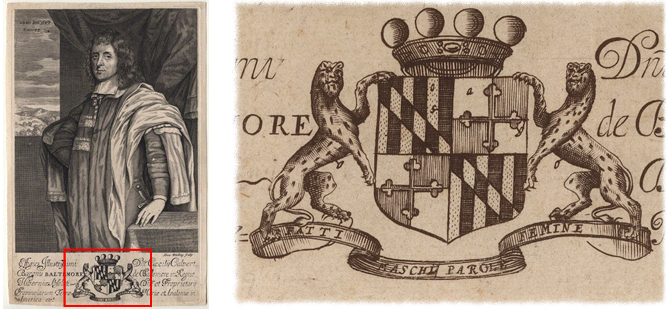

1657 - Portrait of Cecil Calvert that includes his quartered Calvert-Crossland arms. Because the supporters are two leopards, this is Cecil’s personal arms as opposed to the Arms of Maryland wherein the supporters are farmer and fisherman.

Created during his lifetime, this portrait indicates that Cecil asserted the quartered Calvert-Crossland arms as his arms. Nevertheless he continued to occasionally use the same Calvert-only arms his late father used, as for example on coins below. According to Francis Culver: “It was Cecil Calvert, second Lord Baltimore, who introduced into the design of his official Great Seal the armorial bearings of his paternal grandmother, Alicia Crossland; quartering the same with the baronial arms of his father, Sir George Calvert, agreeably to established principles of English heraldry, inasmuch as Alicia Crossland was the daughter and heiress of John Crossland of ‘Crossland,’ in Yorkshire, and the first heiress to marry into this Calvert family.” See: Engraved portrait of Cecil Calvert, second Baron Baltimore, summer 1657; Coakley (1984), p 262; Culver, F.B. (1934), “The Maryland State Flag and Colonial County Colors.” Waverly Press Inc, page 9. |

|||||

1658 - Cecil Calvert had a third Great Seal of Maryland made and sent from England in case the second Great Seal of Maryland was not recovered from Cromwell. The heraldic insignia upon the shield in the Great Seal is Cecil’s quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia. The second Seal of 1648 was said to differ only slightly from the lost first Seal, and the third Seal of 1658 matched 1648 Seal. Apparently all displaying Cecil’s quartered insignia.

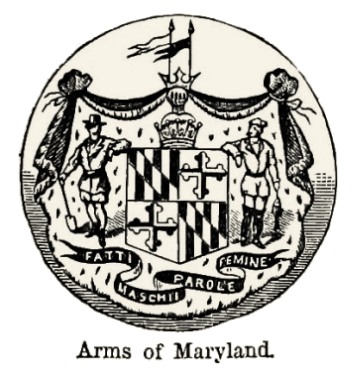

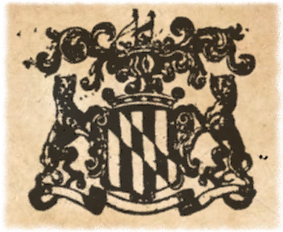

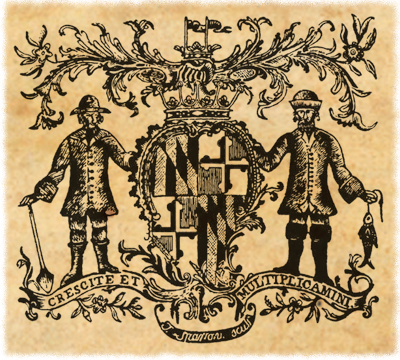

Dies of the Great Seal of Maryland, 1648 or 1658. Cecil Calvert had the third seal sent to Maryland by Captain Josias Fendall, whom he appointed as “keeper of the greate seal” (Boxman, page 701). There is no indication from period sources that Fendall's Seal ceased to supersede the 1648 Seal, which Cecil defined as the Great Seal. The Great Seal is also known as the Arms of Maryland and differs from Cecil Calvert’s personal arms in part by replacing the two leopard supporters (as in 1642) with a farmer and fisherman representing industrious Marylanders. So unlike Cecil’s personal arms, the Great Seal was designed for Maryland specifically and thus its arms with farmer and fisherman are properly the Arms of Maryland.

Various period reditions of Maryland’s colonial arms like these often included the motto “Crescite Et Multiplicamini” even as the official Seal did not. Click to enlarge. While the colonial Great Seal had the Latin motto Fatti Maschii Parole Femine, many period colonial renditions instead had the Latin motto, Crescite Et Multiplicamini. According to historian James Thomas, that motto first appeared on Maryland coins in 1659 (see 1659 below). Notice that the colonial Seal and its renditions always have farmer and fisherman as supporters alongside the shield, whereas Cecil Calvert’s personal arms, sometimes used as a symbol for Maryland, has two leopards as support. See: Hall, C (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, Commission for the Great Seal and Thomas JW (1913). |

|||||

1659 - Cecil Calvert mints a coin with Calvert-only arms on reverse. Within the same timeframe Cecil used either Calvert-Crossland or Calvert-only arms. These coins were to be used in Maryland.

Cecil ran into legal trouble for minting these coins. On October 4, 1659, an arrest warrant was issued for Cecil to appear before the Kings’s Privy Council. Authorities claimed the Charter of Maryland did not permit minting coins. It is said to be unclear the result of that legal intervention, but Cecil’s coins were in use for some years after.

Lord Baltimore Coinage 1658-1659: Introduction, University of Notre Dame Some historians doubt that Cecil’s use of the quartered Calvert-Crossland arms was in keeping with rules of heraldry, because his grandmother, Alicia Crossland, was not a heiress as required by heraldic law for such quartering. It’s possible that Cecil only used his legal arms on his coins to avoid running afoul of heraldic laws, which at the time were legally enforced as trademark law is today. So that may explain why his coins display his Calvert-only insignia rather than his Calvert-Crossland insignia. Cecil’s coins also contained a Latin motto, Crescite et multiplicamini, which means increase and multiply. According to historian James Thomas, the earliest known instance of this motto for Maryland was on Cecil’s coins minted for Maryland. See: Wikipedia: Lord Baltimore penny and Coinfacts: Maryland Sixpence and Coakley (1984), page 262 and Thomas, J (1913), Chronicles of Colonial Maryland, page 229. |

|||||

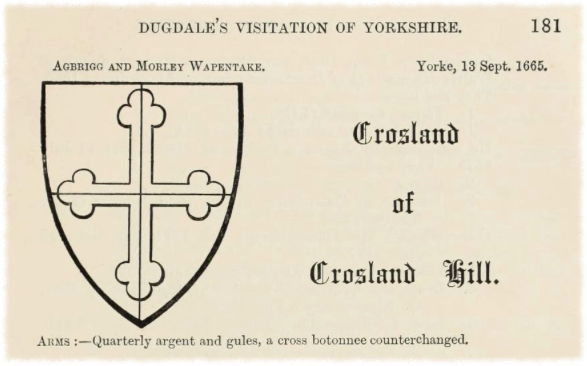

1665 - Official existence of the Crossland family arms (then spelled ‘Crosland’) is confirmed by its inclusion in the heraldic registry Dugdale’s Visitation of Yorkshire seen here.

See: Coakley (1984), Maryland Historical Magazine, p 262 and Dugdal’s Visitation of Yorkshire, 1665. |

|||||

Year 1670 |

|||||

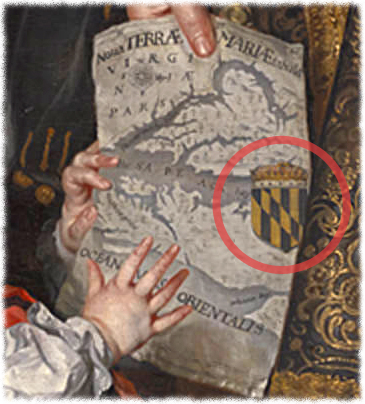

1670 - Portrait of Cecil Calvert includes map of Province of Maryland with Calvert-only arms upon.

Calvert arms on painting of a Map of Maryland. Contrary to the map depicted in this painting, in no source, including the Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, have I found a colonial Maryland map with the Calvert-only insignia. Yet there are several colonial maps listed above and below with Cecil Calvert’s quartered Calvert-Crossland arms. See: 2nd Lord Baltimore, Cecil Calvert (1606-1675). |

|||||

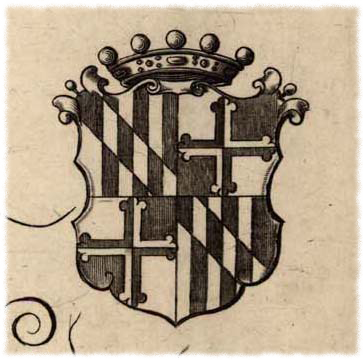

1671 - Cecil Calvert’s quartered Calvert-Crossland arms appears on a map of the Province of Maryland illustrated by John Ogilby.

Calvert-Crossland arms on 1671 map of Maryland. Because the two supporters alongside the shield are leopards, this coat of arms is Cecil Calvert’s, not the Arms of Maryland wherein the two supporters are a farmer and a fisherman. See: Nova Terrae-Mariae Tabula, 1671 and @ raremaps and in Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, p 7. |

|||||

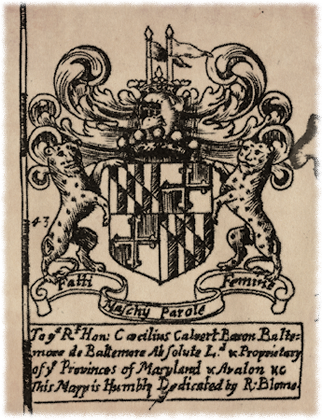

1672 - Cecil Calvert’s quartered Calvert-Crossland arms appears on a map of coastal Maryland illustrated by Richard Blome.

Calvert-Crossland arms on 1672 Maryland map. This coat of arms is Cecil Calvert’s personal arms, not the Arms of Maryland, because the two supporters alongside the shield are leopards. In contrast, the supporters in the Arms of Maryland are a farmer and a fisherman. See: Papenfuse & Coale (1982), Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, page 18 |

|||||

1673 - Cecil Calvert’s quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia emblazoned shield appears on the Map of Chesepeake Bay illustrated by Augustine Herrman.

Calvert-Crossland insignia on shield on 1673 map. See: Library of Congress item #2002623131 and in Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, p 13. |

|||||

1675 - Caecilius Calvert passes away. The second Baron Baltimore and first Proprietor of the Province of Maryland, Cecil Calvert passed away in Middlesex, England on November 30th. Cecil was Maryland’s proprietor for its first forty-two years, yet he never set foot in Maryland, although his family members did. See: Wikipedia: Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore. | |||||

|

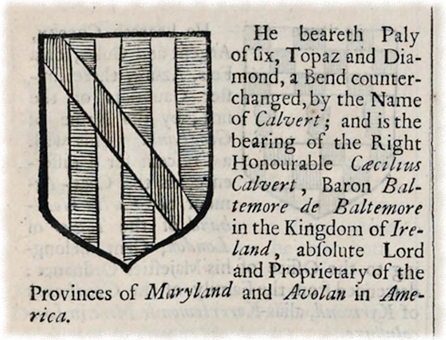

1679 - Cecil Calvert’s heraldic ensign (aka, insignia or escutcheon) in heraldic catalog.

Cecil Calvert is also known as ‘Caecilius Calvert’. Given the official source of this heraldic catalog, the fact that Cecil’s ensign therein is Calvert-only, not Calvert-Crossland, underscores the view among contemporary historians that Cecil’s Calvert-Crossland ensign was not in keeping with heraldic law and may have been of his own fancy. In those days, coats of arms were granted by authority and legally enforced like trademark laws are today. So you were not allowed to invent your own arms. See: A Display of Heraldry (1679), p 279 and Coakley (1984), Maryland Historical Magazine, p 262. |

|||||

1694 - Laws of Maryland published with Cecil Calvert’s personal Calvert-only arms thereupon.

Because the two supporters are leopards, this coat of arms was Cecil Calvert’s, unlike the Arms of Maryland wherein the two supporters are a farmer and a fisherman. The placement of Cecil’s personal arms upon Maryland laws invoked the chain of royal proprietary authority for the Province of Maryland, it is not a reference to the Province itself, as would be the case if the Arms of Maryland were displayed. See: Complete Collection of the Laws of Maryland, cover page. |

|||||

Year 1700 |

|||||

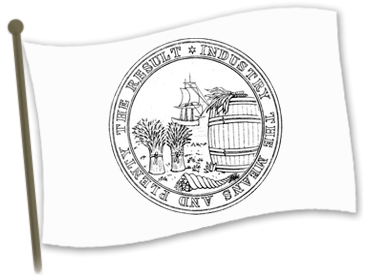

1733 - A Lesser Seal of Maryland appears in Provincial Maryland paper money.

This Lesser Seal was engraved by silversmith Thomas Sparrow and, as with all Maryland Seals, includes the Calvert-Crossland insignia. Unlike the Great Seal but like Cecil Calvert’s coins, both of Sparrow’s Lesser Seals (see also 1765) contained the Latin motto, Crescite et multiplicamini, meaning increase and multiply. See: Wikipedia: Early American Money and Annapolis, City on the Severn, page 87. | |||||

1735 - Map of Maryland and Virginia created by Walter Hoxton includes the Arms of Maryland with its Calvert-Crossland-ensign-emblazoned shield.

Arms of Virginia and Maryland on 1735 map. Because these arms contain a farmer and fisherman, they are the Arms of Maryland, not Cecil Calvert’s personal arms with leopard supporters. The Arms of Maryland never include the Calvert-only ensign (aka, escutcheon). Calvert-only insignia in colonial times refer to Cecil, not to his Province. But this arms refers to Maryland herself. As with Thomas Sparrow’s two Lesser Seals, this arms also has the Latin motto, Crescite et multiplicamini, which means increase and multiply. See: Papenfuse & Coale (1982), Atlas of Historical Maps of Maryland, page 30. |

|||||

1741 - The colonial flag of Maryland was probably recorded in the Proceedings of the Lower House of Assembly (Oct 26, 1742), which includes an invoice of purchases that includes, “A Black and Yellow Flag,” purchased the prior year.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland That description is consistent with a flag emblazoned only with the Calvert-family ensign (aka, escutcheon), rather than the Calvert-Crossland ensign seen on today’s flag. Flags being hand-sown in colonial times, the greater complexity of today’s flag is reason to predict colonial flags would only display the Calvert ensign. See: Spencer R (1914), Provincial Flag of Maryland, page 223. |

|||||

1749 - The colonial flag of Maryland was probably recorded in the Proceedings of the Lower House of Assembly (May 14, 1750), lists items ordered by the Governor and Council the prior year, including “A black and yellow Flag.”

The Colonial Flag of Maryland All descriptions of colonial flags of Maryland are compatible with them being emblazoned with the Calvert-only ensign, as depicted here. No descript ion implies that a colonial Maryland flag resembled today’s quartered Calvert-Crossland Maryland flag. I had hoped to find such a description, alas. See: Spencer R (1914), Provincial Flag of Maryland, page 223. |

|||||

Year 1750 |

|||||

1755 - On August 6, Governor Horatio Sharpe ordered from England a “Black & Yellow Flagg 24 feet long and 16 feet broad with the Union in One Corner.”

According to historian Richard Spencer, this flag was probably not the Provincial Flag of Maryland but was rather intended for “use in his Majesty’s service in the war against the French.” Such wartime use is suggested by the timing of Governor Sharpe’s order (the war with the French starting in 1756) and because along with this flag he ordered barrels of gun powder and four thousand rifle flints. The state of Maryland officially flies this flag today at the Fort Frederick State Park (see). See: Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1753-1761, page 46. Spencer R (1914), Provincial Flag of Maryland, page 224. Wikipedia: Fort Frederick State Park |

|||||

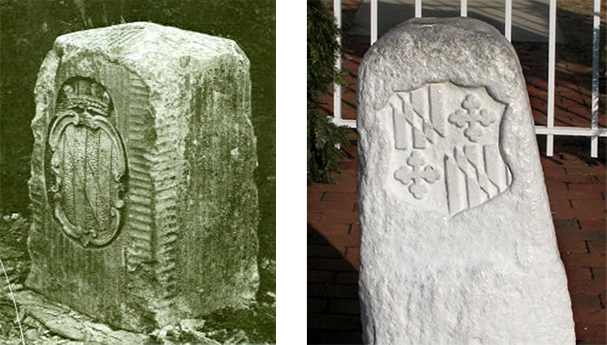

1763 - Cecil Calvert’s ensign was engraved upon Mason-Dixon Line crownstones.

Mason-Dixon Line stones with Cecil Calvert’s two insignia. Some Mason-Dixon Line crownstones display the Calvert-only ensign while others display the Calvert-Crossland ensign. As the history above shows, this ‘either-or usage’ was in keeping with Cecil Calvert’s usage. Cecil died over 100 years before the MDL stones were placed, and no Calvert had been Governor for decades. So the MDL-stone arms suggest a semantic transition of the arms from references to the Proprietor to references to the Province itself. An MDL stone was placed every mile along Maryland’s northern and eastern borders. Every fifth stone was a ‘crownstone’ and only they were engraved with arms. See Wiki: Mason-Dixon Line and History of Western Maryland and MDL Stone with Calvert-Crossland shield. |

|||||

1765 - A Lesser Seal of Maryland engraved by Thomas Sparrow — also known as the Sparrow Seal — appearing upon the cover-page of the Laws of Maryland.

Like Cecil Calvert’s coins, both of Sparrow’s Lesser Seals (see also 1733) contain the Latin motto, Crescite et multiplicamini, which means increase and multiply, an appeal for the health and productive vitality of the Maryland colonists. See: The Laws of Maryland and The Sparrow Seal. |

|||||

| 1776 - Marylanders declare independence from British rule and became the free state of Maryland. On November 11, Maryland’s new Constitution granted authority for creating the Great Seal to the Governor’s Council, declaring,

See: Hall, C (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, page 29 and The Constitution of Maryland, 1776. | |||||

1777 - On March 31, the Governor’s Council decided that the Great Seal of Maryland shall remain the colonial Seal “until a new one can be devised and executed.” See: Hall, Clayton (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, page 30. |

|||||

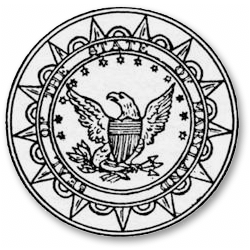

1794 - A new Great Seal of Maryland is devised featuring the Lady of Justice.

Great Seal of Maryland, 1794 With the Great Seal of 1794, Maryland symbolically parted ways with her colonial past by removing any reference thereto. A new Seal for a new (18 year old) State and member of the United States of America. See: Hall, C (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, page 36. |

|||||

Year 1800 |

|||||

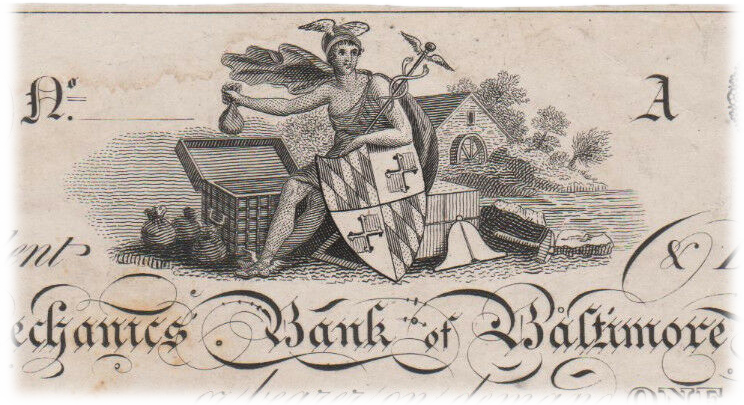

1810s - Unique Arms of the Maryland on Bank of Baltimore 100 dollar banknote.

Appearing on banknote offered for sale on ebay, scan of full bill. |

|||||

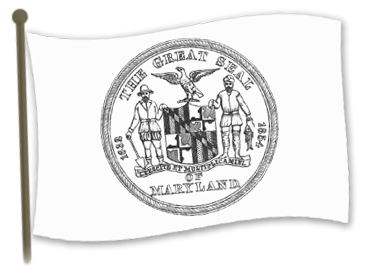

1817 - A new Great Seal of Maryland is issued, and is stripped of any unique symbolism of state identity.

Great Seal of Maryland, 1817 This new state seal being a copy of the Great Seal of the United States of America defined Maryland as a faceless subsidiary of the US, denying the State any unique symbolic identity. This 1817 Seal was used for thirty-seven years, until 1854. Given the question of what designs were used for Maryland flags at given times, it is difficult to imagine this Seal would have been deemed a suitable design. What motivated the creation of this new Seal that stripped away any vestige of Maryland’s unique symbolic heritage? See: Hall (1885) |

|||||

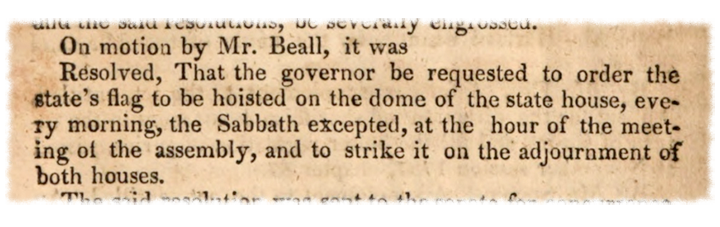

1828 - Maryland House of Deligates resolves to requet that the Governor order the state flag be hoisted daily atop the dome of the state House in Annapolis.

An open question is: What did that Maryland flag hoisted daily look like? Nobody at present can say for sure, but two possible candidates are the Calvert-only design or an 1817 Great Seal design. It is fascinating how things that anyone knew at the time, like what that flag looked like, failed to get recorded and thus ostensibly became lost forever. |

|||||

1832 - fanciful rendition of the Arms of Maryland on a Bank of Baltimore $10 note.

This unique and unofficial rendition of the Arms of Maryland contains the same motto, “Crescite et multiplicamini,” appearing also on Cecil Calvert’s colonial Maryland coins (see 1659 above). The motto means, “increase and multiply.” The Bald Eagle atop Cecil Calvert’s shield, replacing symbols of British Royalty, thoughtfully integrates Maryland’s colonial past with its contemporary membership in the United States. This eagle-over-shield design appears later in the official 1854 Great Seal of Maryland but was not in the Seal at the time this banknote was printed, so its appearance here foreshadowed its appearance in the 1854 Great Sea. Sale on ebay archived @ https://archive.is/aNFcn |

|||||

1838 - Another fanciful Arms of Maryland appeares on a Bank of Baltimore $5 note.

Fanciful Arms of Maryland on Bank of Baltimore note. This is another unique fanciful rendition of the Arms of Maryland, similar to the 1832 rendition above with eagle-over shield and reclining supporters and the “Crescite et multiplicamini,” motto. This rendition was described in The Baltimore Sun (1838) as “the coat of arms of the state of Maryland.” This eagle-over-shield design appearing in the 1830s will later appear in the official Great Seal of 1854. So its appearance here in private use certainly traces creative roots of the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland. See The Vincent Collection, 2008, page 78 and The Baltimore Sun, Oct 22, 1838, page 2. |

|||||

1844 - New order mandates the Maryland flag be hoisted daily as the House of Delegates opens.

The Baltimore Sun, Jan 25, 1844, page 4. It is curious that we saw a similar measure in 1828 above, as if this formality gets repeated. But it raises once again the open question: What did that Maryland flag hoisted daily look like? This also implies that any faithful depiction of the State House at the time might answer that question. |

|||||

1844 - Fanciful Arms of Maryland appears on Maryland Historical Society publication.

The fanciful Arms of Maryland on Maryland Historical Society booklet. This is a different illustration of the fanciful theme seen in 1838 above. So this theme simultaneously saluting the Union with a bald eagle and Maryland’s colonial past with the Calvert-Crossland shield seems to have been popular during this period and may reflect dislike of the then-current 1817 Great Seal of Maryland that was a soulless iteration of the Arms of the United States. See: Constitution of the Maryland Historical Society, 1844, cover and cover page. |

|||||

Year 1845 |

|||||

1845 - The Maryland Historical Society logo includes a unique Arms of Maryland based upon Maryland’s colonial arms with Cecil Calvert’s quartered ensign.

Unique Arms of Maryland in Maryland Historical Society logo. This unique variation on the colonial Arms of Maryland has the two supporters looking over their shoulders at the shield. Its oddly shaped shield resembles the shield in the Sparrow Seal of 1765, with the lower Calvert quadrant halved. See: Discourse on the Character and Life of George Calvert, 1845, cover. |

|||||

1849 - The fanciful Arms of Maryland appears on cover page of book.

Fanciful Arms of Maryland printed on coverpage of book. This timeline is informed only by way of old texts archived online, providing these glimpses into common reproductions of colonial-themed Arms of Maryland during the period from 1794 to 1854 when colonial symbols fell from official use. These glimpses reveal that the quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia never fell from popular use as a symbol of Maryland. And as the next entry shows, there was at least one official use of colonial Maryland arms during that period. This makes it difficult to attribute future uses of Maryland’s colonial symbols to State Rights activists. See: McSherry, J (1849), History of Maryland, cover page. |

|||||

1849 - Maryland State Assembly resolves to contribute a marble stone to the building of the Washington Monument in the nation’s capitol, Washington, DC.

Colonial Arms of Maryland on Washington Monument stone. This Colonial Arms of Maryland was engraved upon Maryland’s contribution to the Washington Monument even though it was not Maryland’s arms at the time. The State Assembly’s choice of colonial arms constitutes official an use thereof and is a good example of the adoration Marylanders have for their founding symbols. Upon completion of Maryland’s block in 1851, an author of a Washington DC newspaper complained about this engraving for referencing Maryland’s colonial past under the rule of Egland.

The Daily Republic, Mar 10, 1851, page 1 It would seem that use of colonial symbols was surprising at that time in early American history, when people still carried the bitter taste of not so-long-ago wars fought against English royalty. In fact, at this time (1849-51) Maryland’s arms were not colonial but republican (see 1817 above). A point on vexillological semantics is worth noting: this underscores that the Marylanders who reintroduced colonial symbols meant them purely as historic reference, not as salutes to English authority. See: Washington Monument Stones, page 4 and Flag Survey. |

|||||

Year 1850 |

|||||

1850 - Banner created by the ladies of Frederick county as a gift to the 8th ward’s Democratic Party for their having gained the largest increase in votes. The article describes the banner thus:

The Baltimore Sun, Nov 2, 1850, page 1 That is the motto upon the Great Seal of 1794 (see above), so the white flag design was probably like this, not assuming any colors that may have been used.

Great Seal of 1794 on flag by Ladies of Frederick. Gifting of flags by the ladies of Frederick and Baltimore was often in the news in those days and the the ladies flags typically represented standards of the day. So it’s possible that Maryland flags at this time were emblazoned with the Great Seal of 1794. There is no surviving trace or clue as to exactly what the government in Annapolis used for the state flag. That this flag in 1850 displayed the 1794 Seal rather than the then-current 1817 Seal (see 1817 above) is curious and might be due to the 1817 Seal lacking any unique State identity, coupled with growing sentiment for State rights / identity. See: The Baltimore Sun, Nov 2, 1850, page 1 and Hall, C (1885), The Great Seal of Maryland, page 36. |

|||||

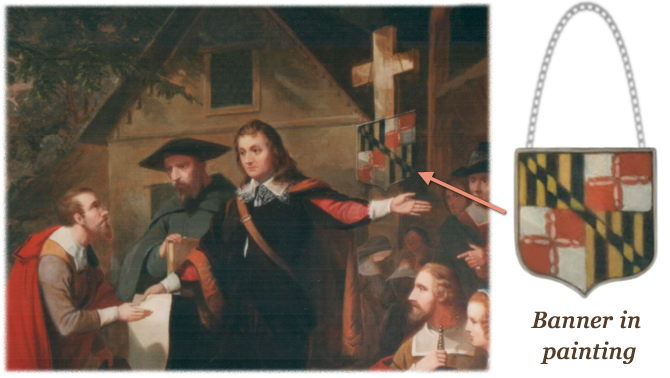

1853 - A banner-style flag of the quartered Calvert-Crossland shield that is very similar to today’s Maryland flag appears in painting by Tompkins Harrison Mattson.

Hung banner in 1853 painting similar to today’s Maryland flag. Mattson’s painting hangs in the Maryland State house and the banner therein is cropped around the Calvert-Crossland insignia, similar to Maryland’s flag today. But unlike the current Maryland flag it is shaped like a shield. Of course this just an artist’s vision of a colonial scene, but in searching for the earliest appearance of the present Maryland flag, this is the closest I could find at the earliest date. See: The Founding of Maryland, by Thomas Mattson, 1853 and in high resolution. |

|||||

Year 1854 |

|||||

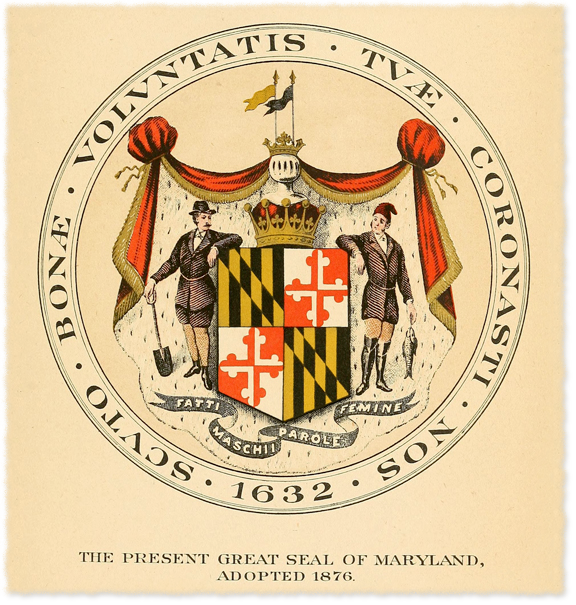

1854 - A new Great Seal of Maryland reintroduces the state’s colonial symbols but with important modifications such as removal of symbols of British royalty and replacement of them with a Bald Eagle to reflect the state’s post-colonial membership in the United States of America.

Great Seal of Maryland, 1854 Governor Louis Lowe ordered this new Great Seal during a lengthly address he gave published in The Baltimore Sun (Jan 9, 1854), wherein he stated,

The Baltimore Sun, Jan 9, 1854, p 1 Gov. Lowe’s comment expresses disenchantment with the then-current 1817 Seal (see 1817 above) because that seal had no reference to Maryland’s history. Indeed, the 1817 Seal erased any unique identity for the State. Such disenchantment might be why the Ladies of Frederick used the 1794 Seal instead of the 1817 Seal for their flag (see 1850 above). Lowe seems to imply that the Arms of the State were understood not to be the then-current Seal of 1817, but to be Maryland’s colonial arms. However, most sources indicate that the Arms of Maryland were whatever the Great Seal was at the time. Different renditions of the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland distinctive by its bald eagle perched over the shield symbolizing the USA click to enlarge The 1854 Seal reintroduced the quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia into official use. But symbols of English royalty in the colonial Great Seal were replaced with a bald eagle, honoring the United States. This creative blending of Maryland’s past and present was previously seen in unofficial Maryland, Arms (see 1838 above). It would seem the sentiments of the author quoted in 1849 above prevailed upon designers of the 1854 Seal to exclude symbols of English royalty. However, this patriotic change will only last 22 years, when in 1876 a new Seal will restore the removed references to royalty. The introduction of the egal in this new Seal was discussed in Zieber, 1897, p21 thus,

It is noteworthy that both authors did not know of any meaning for the eagle being inserted into Maryland’s colonial arms in the Great Seal. It should also be recalled that Maryland’s 1817 Great Seal was entirely America’s bald eagle with no trace of Maryland’s colonial identity having survived, so in fact the eagle did appear earlier than seventy-five years after the Revolution, contrary to Zieber’s account above. My intuition is that the eagle’s introduction was a decision of a committee that came to a compromise, re-introducing the state’s colonial symbols only provided an eagle is included as a pledge of allegiance to the Union. Such a tussle may have marked the onset of the state identity and rights sentiments that would culminate in secessionist rebellion only a few years later. See: Acts of the General Assembly, 1854 and Dulany's History of Maryland and another variant. |

|||||

1859 - fanciful Arms of Maryland on Bank of Baltimore personal check.

The same fanciful rendition of the Arms of Maryland seen on an 1838 Bank of Baltimore $5 note above. This eagle-over-shield design appeared in unofficial printings at least as early as the 1830s but was not incorporated into the official Arms of Maryland until the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland (see above). Sale on ebay archived @ https://archive.is/wip/FjujI |

|||||

1860 - State Rights activists displayed the colonial flag of Maryland in headquarters. As The Daily Exchange reported on November 19:

The Daily Exchange, Nov 19, 1860, page 1. Not surprisingly, this and other incidents to follow show that Maryland’s State Rights activists flew the Maryland State flag, contemporary or colonial, as a symbol of their cause.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland Note that the flag of Baltimore city today is the colonial flag of Maryland with the Battle Monument in Baltimore overlaid. So it is perhaps not too surprising to find the same flag, albeit probably without the Monument, being used there in 1860. |

|||||

1861 - Civil War |

|||||

1861 - This passage, penned by Maryland Confederate General Bradley Johnson, appears to indicate that the colonial flag of Maryland was “the secession flag” at this time.

Johnson, B. (1899), Confederate Military History, page 20. Given that, (1)(a) the 1860 entry above says the colonial flag of Maryland was displayed alongside the South Carolina rebel flag at a State rights club and, (b) here Gen. Johnson says “the secession flag” was likewise flown alongside the South Carolina rebel flag at State rights clubs; and given that (2) Johnson here describes the expanding display of “the secession flag,” which initially appeared only at State rights clubs but after April 18, all Union flags in Baltimore were replaced with the state flag of Maryland, whereupon “the black and gold was everywhere saluted,” it appears to follow that the colonial flag of Maryland was considered “the secession flag” among Maryland’s rebels during the onset of the Civil War in Baltimore.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland The colonial flag represents Maryland’s identity prior to joining the Federal Union, therefore, its use by the rebels symbolized leaving the Union. Georgia’s rebels also revived use of their colonial flag to declare secession. It is reported that after Lincoln was elected, “Rebellion spread rapidly, and the old colonial flag of Georgia was planted at Savannah” (Moore, 1866 p29). The colonial flag of South Carolina also replaced Union flags in Charleston (Breckinridge, 1861, p3). The day Johnson describes above, April 18, 1861, was the day before the first battle with fatalities of the Civil War. While Johnson only refers to Maryland’s colonial flag, descriptions below of April 18th events indicate that a white flag emblazoned with the Maryland State seal was also being used by the rebels. For further accounts of replacing Union with Maryland flags in Baltimore on April 19th, see also Brown (1887) page 64 and Metzner (1911) page 64-5 and Nicolay (1881) page 88 and Harper's Magazine (1866, June), page 17. |

|||||

1861 - Marylander Alfred Marshall Mayer expressed his desire to join the Confederate rebellion by saying he wants to fight under the “old colonial flag of Maryland.”

National Academy of Sciences (1877), Biographical Memoirs, pages 247-8.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland This passage and others reveal that some secessionists saw the colonial flag of Maryland as iconic of their cause. In saying he will fight under the “old colonial flag of Maryland,” he meant he will join the Confederacy, even though the old colonial flag never previously stood for this newly conceived political entity (an interesting point of vexillological semantics). |

|||||

1861 - On April 19, secessionists in Baltimore used a white flag bearing the coat-of-arms of Maryland. The Pratt Street Riot occurred in Baltimore on April 19, marking the start of the Civil War in Maryland. Massachusetts Militia opened fire on rioters, killing 12 civilians. After which a large crowd assembled in protest waving the a Maryland flag consistent with this.

The protesters used a white state seal flag, which at the time would have looked something like this

The Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1861, page 1.

Civilian & Telegraph, Feb 2, 1865, page 2.

American Historical Record, March 1874, page 137.

The New York Times, August 19, 1861, page 3. Clearly the Maryland State flag, in this case emblazoned with the 1854 Seal, was used as a symbol for State Rights, and eventually for secession. A logical symbol for State Rights is the state flag. The day after the riots, on April 20, in a dramatic display of disloyalty Unionists in Baltimore switch teams and sided with the rebels, expressing their change of heart by taking down the Union and hoisting up the Maryland flag.

Nashville Union and American, April 23, 1861. The colonial flag of Maryland again observed in Baltimore as the Civil War began.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland |

|||||

1861 - Confirming the earlier report of a white State flag, the Baltimore Police Marshal George Dodge in a letter described a white Maryland flag that had been seized by police:

Letter Oct 12, 1861. Massachusettes Historical Society (c.1865) p 375. A year later Major Dix described the same captured Maryland flag thus:

Congressional Serial Set (1864) page 617. During 1861, Major Dix imposed a ban on secession colors in Baltimore. These reports reveal that Maryland secessionists prioritized the secession flag (which at the time was the South Carolina secession flag) but would also use Maryland flags as a fallback, or ‘dodge’, to try to circumvent Dix’s ban. So again we see the state flag used by State Rights activists to express their cause. This white Maryland flag seized by police was gifted to the Massachusetts Historical Society by Major Dix and was listed in the society’s collection as relic #94. |

|||||

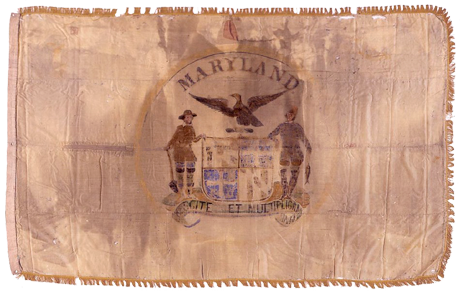

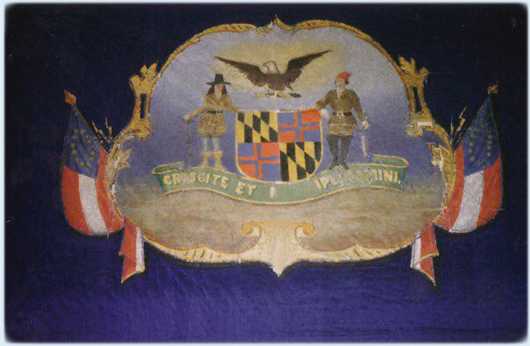

1861 - White flag of the Maryland Guard, who fought for the Confederate State of America.

According to the American Civil War Museum, this Maryland flag with the 1854 Great Seal originated in Baltimore and was smuggled to Richmond, Virginia. It appears to be an aged white flag, which would be consistent with the other reports of white Maryland flags in Baltimore (see above). Note: some information at that linked source is inaccurate. For example, the source claims that the motto on this flag was in the Arms of Maryland from 1777 to 1854. False! In fact the motto only began to be used in 1854. I contacted the museum about the errors and they acknowledged them, thanked me but said they cannot be corrected anytime soon. Now, months later, they remain uncorrected. |

|||||

1861 - The first battle of Maryland’s Confederates was in Manassas, Virginia on July 21, 1861, where they carried a flag with the Great Seal of Maryland, as depicted here.

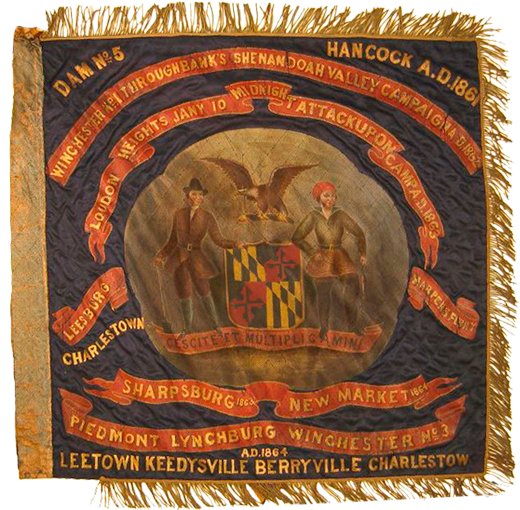

That illustration appears on a certificate of The Society of the Army & Navy of the Confederate States in the State of Maryland (The Huntington Library), and is a scene repeated by other artists. That Battle flag of the 1st Maryland Regiment CSA (aka, the Maryland Line) was preserved after the war and is photographed here.

Battle flag of 1st Maryland Regiment, Confederate Army (Maryland State Archives) The Baltimore Sun reported that this flag was used by the Confederate’s Maryland Line from the first to the last battle of the Civil War:

The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1892. General Johnson’s account suggests that State rights activists were the first to place the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland on a flag. This might support the hypothesis that the reemergence of Maryland’s colonial pre-Union symbols a few years before the Civil War reflected a rise of State rights sentiments. | |||||

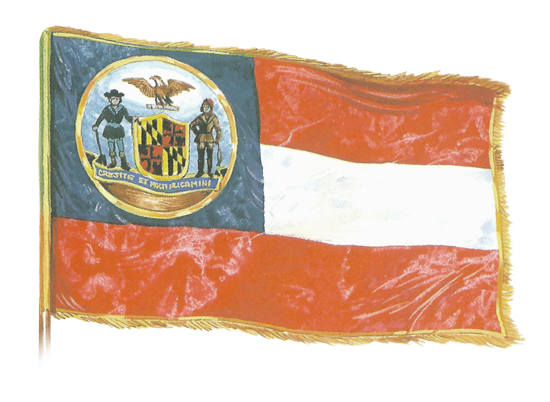

1861 - Battle flag of the 1st Maryland Infantry, Potomac Home Brigade, which fought for the Union flying this flag with the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland.

Union Battle Flag of the 1st Maryland Infantry This flag of a Union militia shows that both Maryland’s rebels and loyalists used the 1854 Great Seal with its quartered Calvert-Crossland shield. Both sides embraced Maryland’s colonial symbols without reservation. The only boycott of symbols was of Union symbols by the rebels. The common use of colonial Maryland symbols by both sides of the Civil War is contrary to the popular narrative that the Calvert-Crossland insignia became divided between Maryland’s warring sides. See: Mosby Heritage Area Association and Moore (2011). | |||||

1861 - Battle flag of the 2nd Maryland Infantry, Confederate States of America.

During the Civil War, both Maryland Confederates and Unionists pledged their allegiance to the quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia as a symbol of their home State. Museum photo @ 2nd Maryland Infantry Colors |

|||||

1861 - Battle flag of the 1st Maryland Calvary, Confederate States of America.

1854 Seal of Maryland on First National Flag of the Confederacy. Marylanders on both sides of the Civil War proudly fought and died under their State’s historic colonial symbols including the Calvert-Crossland insignia. Ironically, by using the 1854 state seal, rebels included the bald eagle symbol of affiliation with the Federal Union they opposed. See: Katcher (2016), Flags of the Civil War, page 122 and The Winder Calvarly Flag Project |

|||||

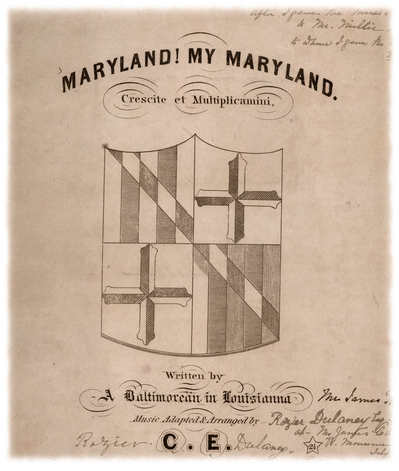

1861 - Cover of original songbook for the rebel song Maryland My Maryland.

Miller (2011). Maryland, my Maryland! Remembering the Pratt Street Riot |

|||||

1861 - The Confederate Maryland Line under General Bradley Johnson used small swallow-tail flags, or guidons, with the cross bottony. While this flag may reference the Crossland arms in the Great Seal of Maryland, because its coloration is not counterchanged, it is technically not the Crossland-family arms.

Another flag of the same design served as the headquarters flag for General Johnson. As we shall see, General Johnson had a personal attachment to the cross bottony, which he saw as a symbol of religious liberty. Maryland’s Confederates were not the only ones using the cross bottony on swallow-tail flags. Here we see Maryland’s Union General Alfred Howe Terry posing before a large swallow-tail flag with the cross bottony upon.

These are the only Civil War flags from Maryland featuring just the Maryland cross that I can locate after extensive archival research. Both sides placed the Maryland cross on swallow-tail flags, which contradicts the theory that the two sides split over the quartered ensign with only the Confederates using the Maryland cross on flags. |

|||||

1861 - A “secessionist cockade” worn by Marylanders who supported secession.

Secession ribbon with Maryland Arms The 1854 Great Seal of Maryland with Calvert-Crossland insignia appears on a button in the center of a cockade ribbon worn by supporters of secession shortly before the Civil War broke out. It is a bit ironic that Maryland’s rebels used the 1854 Seal throughout the Civil War given that it includes the bald eagle that served as reference and salute to the Union they were at arms against. Maryland’s Confederate soldiers wore name badges shaped as a Maryland Cross, from the Crossland family arms in the state arms.

This Maryland Cross badge belonged to Confederate Private Gresham Hough of the 1st Maryland Cavalry, CSA.

Confederate soldiers also wore this belt buckle with the Great Seal of Maryland including the Calvert-Crossland quartering as in today’s flag. In fact, Maryland’s Confederates had at least two different belt-buckle designs each with the Calvert-Crossland quartering in the state seal. |

|||||

1862 - Advertisement for badges of the Maryland coat of arms specifically for the Maryland Line (CSA), sold from Richmond, Virginia, Confederate territory.

Appearing in the Richmond Dispatch, Sept 17, 1862, this ad suggests that the Maryland Line acquired their badges from H. H. Kayton, Letter Cutter, possibly including their Maryland Cross badges. |

|||||

1865 - Civil War Ends |

|||||

1865 - The election of Richard Grason in 1864 to Judge of the Circuit Court of Baltimore County was nullified after the Committee on Elections determined he sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War. The Maryland State flag played a central role in the Committee’s decision to nullify:

Report of the Committee on Elections in the Contested Election Case of James L. Ridgely vs Richard Grason, 1865. The fact that Grason joined an informal militia that wore State badges and flew a State flag in the absence of a Union flag was taken as sufficient evidence of his sedition, thereby nullifying his election to Judge. It was common knowledge that the state flag with the 1854 Great Seal was used by rebels as a symbol for their cause. The transcript of this case reveal how important the Maryland State flag was in the prosecution of Grason (see). |

|||||

1866 - This is the earliest official statement I have found of exactly what the Maryland flag was, attributed in a textbook footnote to the Maryland Secretary of State:

Preble GH. (1880) History of the flag of the United States of America, page 622. Footnote 1 in that book not only reveals what the official Maryland flag was in 1866, but that an official on behalf of the state asserted that the state had a specific flag, thirty-eight years before an official Maryland flag would be codified into law in 1904 (that flag being today’s Maryland flag). Another insight from this footnote is that the arms of the U.S. appeared on the reverse side of the Maryland flag. That was also a feature of State flags used by Maryland Unionists during the Civil War. Including U.S. arms asserted Maryland’s membership in the Union. That is why it played a role in the Election Committee’s investigation of Richard Grason (see 1865 above), wherein witnesses were asked if Maryland flags seen where he collaborated with others had any other device on the reverse side (as here and here), as a test of whether or not Grason’s affiliations were among loyalists or rebels whose flags would exclude U.S. arms. It should be noted that the state seal appearing in the textbook quoted above was not the state seal at the time of the letter from Secretary of State Carter in 1866, but was the state seal at the time the book was first published in 1880. But consistent with the Secretary’s letter, the state seal was emblazoned Maryland flags after 1876 as well. |

|||||

1868 - Ladies of Baltimore present the Ninth Regiment with a Maryland State flag.

The Baltimore Sun, Mar 13, 1868, page 1. At the presentation of this flag to the Ninth Regiment, Colonel E. T. Joyce said...

The Baltimore Sun, Mar 18, 1868, page 1. That passage from Joyce’s speech presents an especially poignant elucidation of the deep meaning and pride residing in the Arms of Maryland, carried through from colonial times to present. |

|||||

1871 - The Society of the Army and Navy of the Confederate States of America in the State of Maryland was founded and had this badge created:

Proceedings of the American Numismatic and Archeological Society, 1903, page 61.

Maryland Line Confederate Soldiers’ Home, page 95. Maryland’s Confederate veterans often used the Crossland, or Maryland, cross in memorial symbols. |

|||||

Year 1875 |

|||||

1875 - Maryland Confederate veterans wear a badge with the Arms of Maryland at the memorial dedication of a bronze statue of Confederate hero Stonewall Jackson. As The Baltimore Sun reported:

The Baltimore Sun, Oct 25, 1875, page 4. I have not been able to find an image of that badge, but apparently it included to full state seal. |

|||||

1876 - The Westminster, MD newspaper The Democratic Advocate published an editorial position objecting to a bill before the Maryland House of Delegates to change the 1854 Great Seal. The proposed change intended to restore the Seal to its original appearance in colonial times.

The Democratic Advocate, March 18, 1876, page 2. While the author proposes that restoring symbols of English royalty reflects “a returning reverence for the crown,” the intention was simply to honor Maryland’s history to its roots. This raises a point of vexillological semantics (given that the proposed change would pass and adorn Maryland’s flag until 1904): Reference to an authority in a flag may not necessarily reflect allegiance to that authority. |

|||||

1876 - A New Orleans newspaper describes a Maryland flag in a proposal from a Maryland State commission regarding their appearance at the American Centennial Celebration.

New Orleans Republican, March 26, 1876, page 1. This description of a Maryland flag is most consistent with the state seal flag. While it is technically an error to say the state seal flag has “the coat of arms of Lord Baltimore,” which has two leopards alongside the shield whereas the Arms of Maryland has a farmer and fisherman, the flag’s squarish height to width is consistent with the state seal flag. |

|||||

1876 - A new Great Seal of Maryland is approved, restoring many colonial features and maintaining use of the quartered Calvery-Corssland arms since the prior Seal of 1854.

The 1876 Seal closely restored Maryland’s colonial Great Seal of 1658, although there are minor differences as for example the wind-blown directions of the small swallow-tail flags, as seen in these period prints of the 1658, 1854 and 1876 Great Seals of Maryland (while the colonial Great Seal officially had the Latin motto Fatti Maschii Parole Femine, most period renditions had the motto that reappeared in the 1854 Seal, Crescite et Multiplicamini): Period renditions of Maryland’s Seals with Calvert-Crossland ensign, click to enlarge The 1876 Seal removed the reference to the United States that the 1854 Seal had introduced, specifically a bald eagle perched above the Calvert-Crossland shield. In 1854 the eagle replaced references to English royalty in the 1658 Seal. Objection to the restoration of symbols of the crown in 1876 is quoted in an 1876 timeline module above. Contrary to the fears of the critics, it turned out that the change did not reflect a returning reverence for English subjugation but simply honoring the state of Maryland to its origins. In my opinion the 1854 Seal was the most creative and meaningful. |

|||||

Year 1880 |

|||||

1880 - Advertisment in The Baltimore Sun, October 4th, reads: “Maryland State Flags, In Yellow and Black and White and Black.

The Baltimore Sun, Monday, October 4, 1880, page 2. There is no known Maryland flag that would fit the described four-color scheme of “yellow and black and white and black.” The closest four-color scheme for a known Maryland flag would be yellow and black and white and red, the scheme of the current Maryland flag, differing from the scheme described in this 1880 advert by only one color, suggesting the possibility of a type error using ‘black’ in place of ‘red’. This advertisement was run for several days prior to the 150th anniversary of Baltimore city where the first documented instance of the current Maryland flag was captured by the artist Frank Mayer, seen below. A possible way red might have been transposed to black could be due to an error in the 1854 Great Seal of Maryland that was corrected in 1876, just four years prior to this advert. In Clayton Hall’s pamphlet on the Seal, he mentions that an error the Seal was “the portions of the shield which are properly red, were represented as black.” So, if you were a flag maker who wanted to portray the shield as found in recent depictions, you might have done so with yellow and black and white and black, as the advert above describes. |

|||||

1880 - The 150th anniversary of the City of Baltimore – Baltimore’s Sesquicentennial Anniversary – was an affair for which thousands of flags were produced and displayed. One of those flags was illustrated here by the artist Frank Mayer and stands as the oldest known recorded instance of the contemporary State flag of Maryland.

Maryland flag in sketch by Frank Mayer, 1880 Stiverson, Gregory, in Unlocking the Secrets of Time: Maryland's Hidden Heritage, 1998, pages 4-12. Mayer sketched this scene at the 150th anniversary of Baltimore city. This sketch was found by historian Gregory Stiverson. I’ve spent countless hours trying to find any earlier instance of our current Maryland flag, alas, to no avail. But I did find other instances clues in records of the 150th anniversary of Baltimore suggesting that this flag design might have been in common if not official use. Here we see shield-shaped banners with the quartered Calvert-Crossland insignia seen hanging from windows during Baltimore city’s Sesquicentennial Anniversary celebration, October 11-19, 1880.

Buildings on Baltimore Street decorated during Baltimore’s Sesquicentennial Anniversary (Digital Maryland Collection) This is the first photograph in our timeline, and it show flags with the Calvert-Crossland insignia matching the shield-shaped flag in T. H. Mattson’s painting above (see 1853 above). I believe that this building seen above on Baltimore Street was the office of The Baltimore Sun described in the following news report about the anniversary celebration.

The Baltimore Sun, October 12, 1880, page 6. That is a perfect description of the building in the photo above, also on Baltimore Street. But the important part is that, “Over the first story are small flags bearing the quarterings of the shield of Maryland.” Given that the author describes banners with quartered Calvert-Crossland arms hung from windows, as seen above, and then describes that there were additionally “flags bearing the quarterings of the shield of Maryland,” that second quartering must be on proper flags, not shield-shaped banners, and thus almost certainly were flags matching the contemporary Maryland flag. Unfortunately the flags along the first floor in the photo (see source) are blurred due to waving during the slow exposure of the antique camera. |

|||||

1882 - A description and history of the Maryland State flag consistent the Great Seal flag appears in the following short blurb appearing in a Westminster, Maryland newspaper.

The Democratic Advocate (Westminster, Md.),

|

|||||

1882 - Select Committee finds Maryland’s Great Seal of 1876 problematic.

The Baltimore Sun, Jan 16, 1882 page 4. The Select Committee was appointed by General Assembly of Maryland on March 24, 1880 to determine if the 1876 Great Seal “is the true seal of the State as required by Joint Resolution No. 5, passed by the General Assembly at its Session in 1876.” Despite the Committee’s negative conclusion, the 1876 Seal remains the Great Seal of Maryland to this present day. See: Proceedings of the House of Delegates of Maryland, January Session, 1882, page 1486. |

|||||

1886 - Confederate flags with the Great Seal of Maryland, carried at the dedication ceremony of the Monument of Maryland’s Confederate soldiers who died at the Gettysburg battlefield.

Southern Historical Scoiety Papers, Vol 14, 1886, pages 437-8. The descriptions of these two flags are consistent with the official Maryland flag at the time, the Great Seal against blue silk and carried by Confederates during the Civil War.

Battle flag of 1st Maryland Regiment, Confederate Army |

|||||

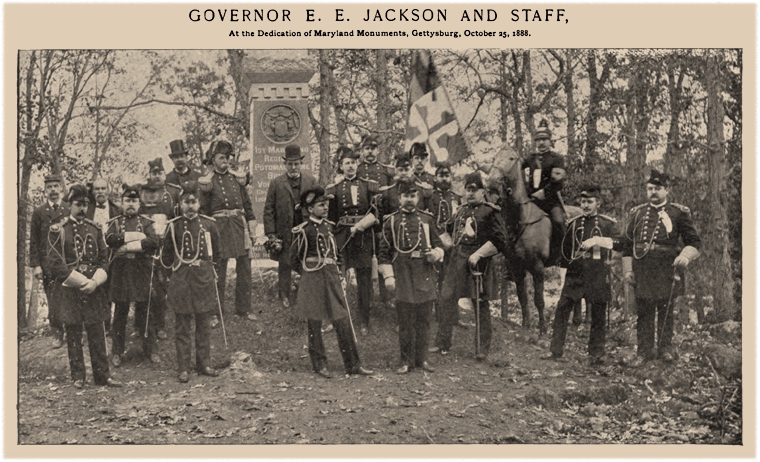

1888 - Earliest known photograph of today’s Maryland flag, carried at the dedication ceremony of the Monument to Maryland’s Union soldiers who died in the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863).

The report of the Gettysburg Monument Commission, published three years after the monument’s dedication ceremony, indicates that the appearance of the contemporary Maryland flag design at the ceremony on October 25, 1888 was its first official use. The Commission’s report states:

Report of the state of Maryland Gettysburg Monument Commission, June 17, 1891, page 38 and page 79. That description of a Maryland flag “used for the first time” tends to imply that its design, the same in use today, was a new sight in 1888. Another interpretation is that the author is noting that this particular Maryland flag was brand new. The first interpretation means that our contemporary Maryland flag had never been officially used prior to this Gettysburg ceremony. However, unofficial use of the same design is known to have occurred at the Baltimore-city anniversary eight years prior (see 1880 above). Maryland’s Union veterans organized to have this monument erected in response to Confederate veterans who erected a Gettysburg monument to their fallen comrades two years prior (see 1886 above). |

|||||

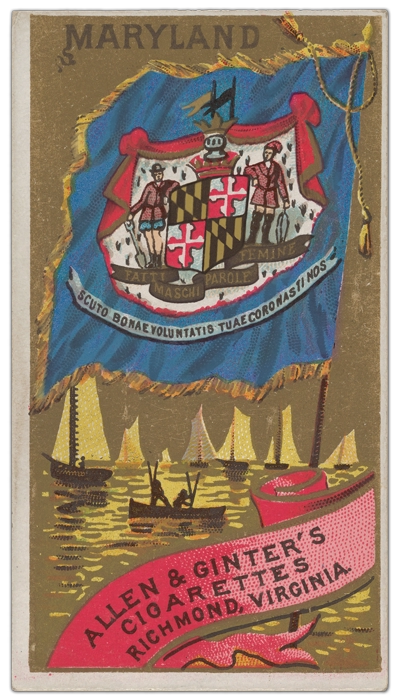

1888 - Cigarette card displays the official Maryland State flag of the time, with the state seal.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Trade cards from the ‘Flags of the States and Territories’ series (N11), issued in 1888 in a set of 47 cards to promote Allen & Ginter brand cigarettes. There are also approximately 100 scroll color variations. The museum’s collection contains the full set of 47 cards, as well as 54 scroll color variations and one cutout card.” This card demonstrates the continuity of the blue-backed state seal flag from at least the Civil War (above) to this year of 1888, and as we shall see (below), later still. |

|||||

1889 - Maryland’s Fifth Regiment presented with today’s quartered Calvert-Crossland flag:

The Baltimore Sun, October 15, 1889, page 4. The description of a Maryland State flag of “yellow and black, red and white” can be no other than today’s Maryland flag. At this time, “Maryland, My Maryland” was not the official state song (not being adopted as such until 1939). Given that it was a battle hymn of the Confederacy during the Civil War, its presentation at this ceremony of the Fifth Regiment is consistent with the Regiment’s long-standing sympathies to the Confederacy that were so strong the Regiment carried the Confederate stars and bars flag at events into the 1950s. |

|||||

1889 - Maryland Confederate veterans group presents the Maryland Cross in Calvert colors at a memorial to Confederate hero Jefferson Davis. The cross was made out of pansy flowers.

The Times Herald, December 7, 1889, page 1. This and many other examples above show that Maryland’s rebels had no aversion to Calvert colors. |

|||||

1890 - Maryland Confederate veterans attend Robert E. Lee memorial in Richmond, Virginia carrying today’s Maryland flag with the quartered Calvert-Crossland ensignia.

The Baltimore Sun, May 28, 1890, page 3. The same news report describes two Maryland badges worn by Maryland’s memorial attendees.

The Baltimore Sun, May 28, 1890, page 3. The first badge described sounds like the Confederate Army and Navy badge shown above (see 1871), while the second badge features the Maryland Cross (aka, the heraldic insignia of the Crossland family) at the center of the badge surrounded by black and gold frill. That second badge is another prime example of Maryland Confederates using the Maryland Cross an icon of their identity. This is consistent with General Bradley Johnson’s enduring idolization of the Maryland Cross as a symbol of religious liberty. |

|||||

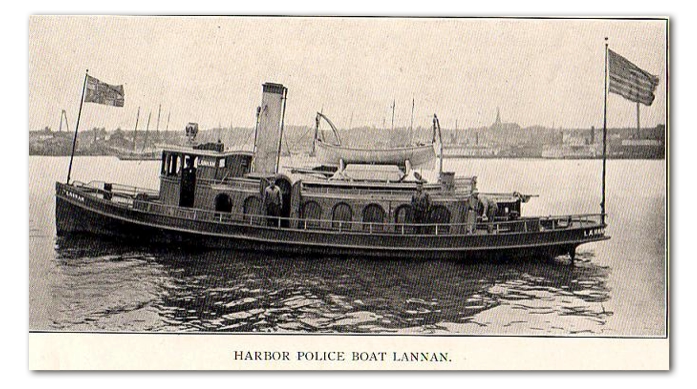

1891 - Quartered Calvert-Crossland Maryland flag, same flag used today, flown on the Lennan, a patrol boat of the Baltimore City Harbor Police. To see the flag, you may need to click on the image to enlarge it. Baltimore City Police Department's Marine Unit The Maryland flag of today appears on the left, the boat’s forward flag, and it is the same Calvert-Crossland ensign flag in use today. This might be the second oldest photograph of today’s Maryland flag (see 1888 above for the oldest known photo of this flag type), which was not yet codified into law as the official Maryland flag (which happens in 1904) at the time this photograph was taken. |

|||||

1892 - An article in the Baltimore Sun reveals important historical facts about the Maryland flag used by Maryland’s Confederate soldiers during the Civil War at a July 4th meeting of the Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1892, page 8. The flag that Johnson refers to is this Maryland flag, carried by Maryland rebels during the Civil War.

Battle flag of 1st Maryland Regiment, Confederate Army (MSA) The passage above is confusing because it first describes the expected Maryland flag design of the time to be “gold and black bars and crosses of red and white,” with no further detail given. That sounds perfectly like the state flag we know today, comprised only of the Calvert-Crossland ensign, which is but a subset of the full coat of arms of Maryland. However, the author then says Johnson’s flag is “the Maryland flag as generally recognized,” which means the expected Maryland-flag design in 1892 would include the full Maryland coat of arms, with the farmer and fisherman alongside the ensign fit onto a shield. That confusing passage speaks to an open question, which is: How common were usages of our contemporary Maryland flag in the 1890s, after its first official use in 1888? While our contemporary Maryland flag began showing up in some places, at least as early as 1880, the state seal flag continued to also be used in the 1890s, as we shall see in the next year at the World’s Fair. This confusing state of affairs — two flag designs for one State — likely prompted legislation in 1904 that made our current Maryland-flag design the one and only official Maryland State flag. |

|||||

1892 - The Maryland Historical Society orangaized a memorial ceremony of colonial Maryland soldiers who fought against the British in the Battle of Guilford Court House in Greensboro, NC in 1781. This passage describe use of the Calvert-arms-only flag used in colonial times.

Extracts from the Memorial Volume of the Guilford Battle Ground Company, page 3.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland This passage confirms that in 1892, the Maryland Historical Society believed that the colonial flag of Maryland was the Calvert-only flag, as the Society and historians believe to this day. The relevance of this point is that in a few years, 1900, a strange effort would be made to, against all evidence, propagate the false belief that the colonial flag of Maryland was our current Maryland flag with Calvert and Crossland arms quartered (see 1900 below). That false belief bolstered support for passage of a law in 1904 that made our current Maryland flag the official state flag. |

|||||

1893 - In a souvenir booklet on Maryland printed for the World’s Fair, this history of the state flag was given, and it describes the Maryland flag of our present day.

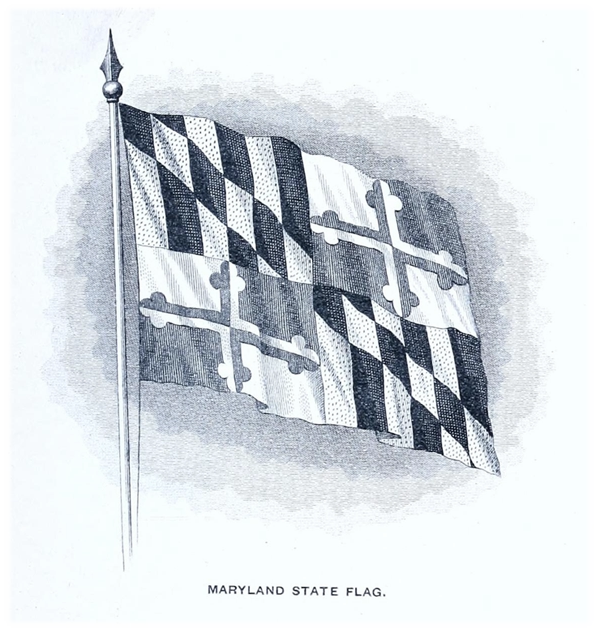

Maryland, Its Resources, Industries and Agricultural Condition 1893, p 16. That publication, printed for the 1893 World’s Fair, contains this beautiful etching of the Maryland flag.

Maryland, Its Resources, Industries and Agricultural Condition 1893, page 1. |

|||||

1894 - Report in the Baltimore Sun mentions use of Maryland Cross badges during the Civil War (see the last 1861 entry above).

The Baltimore Sun, March 24, 1894. However, this description of multi-colored badges does not fit the examples seen above in 1861. |

|||||

1894 - Maryland Confederate veterans, including Gen. Bradley Johnson, attend an unveiling of a monument to CSA soldiers and sailors. The Maryland Confederates arrived at West Point, Virginia, on boat flying the colonial Maryland flag.

Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol 22, page 376. The description of this flag being “sable and gold,” as well as its “glittering” (consistent with the high contrast of black and gold), as well as being “the old banner” indicates that the Confederates used the old colonial Maryland flag, as they had in some instances during the first days of the rebellion during 1860 in Baltimore that led to Civil War the following year.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland Apparently, even into the late nineteenth century, Maryland’s Confederate veterans embraced colonial symbols of the State, which denote its identity outside the Federal Union they fought against. |

|||||

1894 - Maryland’s Fifth Regiment was a stronghold of Confederate sympathies even well into the twentieth century. This report in The Baltimore Sun described the scene at the Fifth Regiment Armory in preparation for a large reception.

The Baltimore Sun, Oct 2, 1894. Just as a name for the American flag is “the red, white and blue” a name for the colonial flag of Maryland is “the gold and black.” Therefore, the most straightforward reading of this passage is that, 29 years after the Civil War, the Confederate sympathetic Fifth Regiment was proudly hoisting the Calvert-only colonial flag of Maryland.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland |

|||||

| 1895 - Why did Maryland’s Confederates give particular attention to the Maryland Cross? A plausible answer is General Bradley Johnson’s fascination with it, which he called the Cross of Avalon. The Baltimore Sun recorded this excerpt of a lecture he gave years after the war where he presents the cross as a symbol of Maryland’s religious liberty.

The Baltimore Sun, Mar 26, 1895, page 8. |

|||||

1898 - Maryland flag with Great Seal presented by a committee of ladies to the Fifth Regiment.

The Baltimore Sun, May 7, 1898, page 10. The passage describes a customized variant of Maryland State Seal Flag.

|

|||||

|

1900 - A textbook Chronicles of Colonial Maryland by historian James Thomas is published. Thomas claims therein that the colonial flag of Maryland was “composed of the armorial bearings and colors of the Calvert and Crossland arms, quartered,” just like the state’s contemporary flag. He also claimed that today’s Maryland flag had been in use continuously since colonial times. However, his claims are contrary to the consensus of historians and available evidence. Thomas’ unsubstantiated history of the colonial flag of Maryland was used by lawmakers four years later in 1904 to justify passage of a law that made Maryland’s current state flag the first legally specified flag of Maryland. Thomas’ role in that flag law was so significant a booklet published by the state Governor eighteen years later gave him credit for its passage (Tilghman, 1922, page 27). The 1904 Maryland Flag Act encoded Thomas’ fanciful flag history into law and even cited it as the leading of two reasons for the law, that the legal flag should be the state’s colonial flag. It states,

This passage from the flag law shows that one of the two reasons for it was to make the state flag match its colonial flag. So, according to the reasoning in the law, Maryland’s official flag ought to be what the only evidence we have says the colonial flag was, the Calvert-only ensign, not the Calvert-Crossland quartering the law errantly describes.

The Colonial Flag of Maryland Examining Thomas’ claims, he cites three instances where the Maryland flag was used in colonial times (pages 248-50), for which he cites three sources. He first cites the use of the colonial flag when Lord Baltimore arrived on Maryland’s shore, but his source for this, British Empire in America, only refers to the flag as “the Colours” with no further detail. So his source does not support his thesis. Next Thomas mentions the colonial flag being used during the Severn battle in 1655, citing Bozman’s History of Maryland (pages 525 and 697). However, Bozman merely mentions “lord Baltimore’s colours” being used during the battle, giving no greater detail about that flag. So this source also failed to support his theis. In contrast, another source available at the time, but that Thomas was apparently unaware of, reported eyewitness testimony of the Severn battle from Captain Roger Heamans, who recalled observing Maryland’s colonialists, “marching with drums beating, colours flying, the colours were black and yellow, appointed by the Lord Proprietary ” (quoted by Scharf, 1879, page 220). That firsthand description of the colonial flag is consistent with the black and yellow Calvert-only flag cited throughout this timeline. Thomas then cites two other historical instances of the use of “a Maryland flag,” (1) during the expedition against Fort Duquesne in 1756 and (2) during the Civil War by the Confederate Frederick volunteers. His source for these is “Hollander, ‘Political Institutions’,” which I cannot locate. However, we know that the Frederick volunteers flag, which survived the war, was a state seal flag (see 1886 above). Furthermore, it is unlikely that Hollander proves the thesis because Thomas himself only asserts that it evidences that a, not the, Maryland flag was used at these two times, apparently conceding that those flags may have not been the Calvert-Crossland quartered flag he implies they were. It is curious that a fanciful narrative about the colonial flag of Maryland popped out of nowhere (appearing at least in a state publication in 1893 and then in Thomas’ book in 1900) and was used to justify the 1904 law making the Calvert-Crossland quartering the state flag, after which the fanciful narrative vanished. Did Thomas and perhaps others deliberately propagate a false history to ensure the Calvert-Crossland flag — a flag for which there is no evidence of existence before 1880 — became the only legal flag? |

|||||

|

1901 - A news report about the World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, reveals that a Maryland flag with the state seal was being used by the official Maryland presentation at the Fair.

The Baltimore Sun, May 22, 1901, page 10. That the Maryland flag described had a latin motto means it was the state seal flag, not the newer design with only the Calvert-Crossland ensign. Note also that the author refers to it not as a Maryland flag but “the Maryland flag,” suggesting that the state seal flag was still in common use into the twentieth century.

It is noteworthy that the official Maryland presentation at the 1893 World’s Fair used our contemporary Maryland flag while eight years later at the 1901 World’s Fair the official presentation reverted back to the earlier state seal flag. This demonstrates a confusing state of affairs for Maryland’s vexillological identity at this time, an ambiguity that would be resolved three years later with the formal codification of the current Maryland State flag. |

|||||

|

1904 - The Calvert-Crossland quartered flag is legally enshrined as the officical state flag of Maryland. As detailed in the 1900 section above, the historical claim in this law that the legalized flag had been in use by common consent since Maryland’s colonial founding has no supporting evidence, is contradicted by available evidence and is therefore rejected by the consensus of contemporary historians. There is no evidence of a Calvert-Crossland quartered flag before 1880 when Frank Mayer illustrated one held by an attendee of a public event (see 1880 above). In contrast, there is evidence we have reviewed above that the colonial flag was the Calvert-only flag. The reason I embarked upon this research project was in hopes of finding an earlier occurrence of our contemporary Maryland flag. Alas, after exhaustive efforts I have relented to the possibility that 1880 saw its first instance. Although I will probably never be convinced that its likeness never existed before then and some long-forgotten record of it may still be out there somewhere. It is, after all, nothing more than a direct extraction of the escutcheon within the state seal. |

my journal

my home page

Maryland House of Delegates Journal, 1828-27,

Maryland House of Delegates Journal, 1828-27,